Artificial fear inteligence of death by Lauren Huret (english)

Ce document a été numérisé dans le cadre du projet international EUCIDA (2017/2020) regroupant l’Espace multimédia Gantner (France), Ruared (Dublin, Irlande), Luznava Manor (Rezeknes, Lettonie)

EUCIDA (EUropean Connection In Digital Art), des connexions européennes pour les arts numériques, est un projet sur trois ans, financé par creative europe, porté par le centre d’art RUARED (Irlande). Ce projet a pour objectif à travers une plateforme collaborative, de rendre plus visible internationalement, le champ des arts numériques et ses pratiques innovantes afin de les développer d’avantage et durablement.

The many examples of applied artificial intelligence, or “weak AI,” that now populate our lives (Siri, Internet search engines, chatbots, auto-translate, facial recognition, etc.), developed by major tech companies and secular institu–tions, foreshadow the presupposed future appearance of a form of non-organic autonomous intelligence. Such abun–dant use of weak AI is very recent but sociological and behavioral studies suggest we have a “natural” empathy and powerful emotional reaction vis-à-vis these objects/programs and their representations (user interfaces).

In fact, forms of non-organic intelligence are already sur–rounded by stories, behaviors, and personifications as well as political and social claims. We must constantly face, in–tegrate, and learn what functions they serve and the phe–nomena associated with them. We must continually try to make sense out of what we may feel, live, and experience with, in, and around these machines with the help of narra–tives, mythologies, re-appropriations, and interpretations, like the ones manifested in the latest science fiction movies. AI has an undeniable attraction on our imagination, and it opens an infinite field of exegesis, interpretative shifts, in–describable confusion and stupor. Despite the many philo–sophical questions that arise (e.g. What is intelligence?), tremendous breakthroughs in the last few years have brought AIs much closer to us.

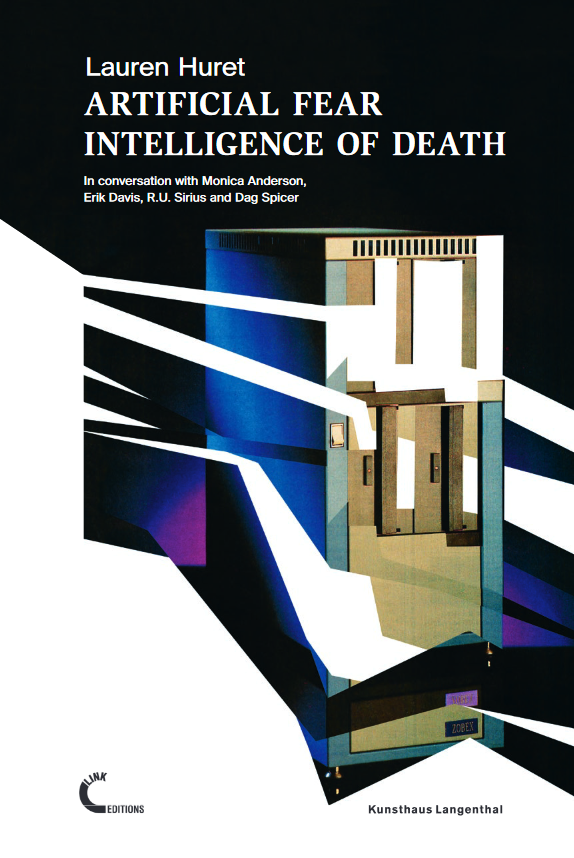

Beginning in 2013, I started delving into the myriad of tech–nical, philosophical, and sci-fi literature surrounding AI as well as its role on the internet. In the summer of 2015, with support from the FCAC Geneva, I undertook a trip to the San Francisco Bay Area and the epicenter of computing: Silicon Valley, California. I wanted to talk face to face with thinkers who could offer varying perspectives, profound criticism, funny, scary, and humbling insights, and an overview of artificial intelligence. For this publication, I have selected the interviews that I conducted with Monica Anderson, Erik Davis, R.U. Sirius, and Dag Spicer because they reflect a multiplicity of viewpoints and the complexity of AI. During my visit to the Prelinger Archives in San Francisco, Megan Prelinger introduced me to Byte magazine, an important and popular monthly magazine from the early days of personal computers. Visual material from issues of Byte from 1978 to 1986 forms the basis of the collages in this book. When looking through this iconic material, it was evident that the invention of personal computers was about to impact every level of society in a major way. Often compared to a magical object with fantastic abilities, the computer has been seen—since its inception—as a “miracle.” From the same source I chose a selection of advertisements in which computers are ascribed human or magical qualities, resonating, often in a goofy and playful way, with the notion of a human-like computer that is so central to AI discourse.

I invited Hunter Longe to collaborate and assist in my knowl–edge-gathering excursion, of which this book is one of the outputs. His voice is present in several of the interviews. Without him the project would not have been possible, not only because he is originally from the Bay Area but because his knowledge on the topic made him an irreplaceable dia–log partner. I would like to thank him, his family, and his friends who have been so kind and supportive. I would also like to thank the interviewees who were extremely generous with their time and thoughts, as well as Raffael Dörig and Claire Hoffmann for all of their work and for believing in the project.

Lauren Huret, April 2016